Artificial intelligence is unquestionably altering intelligence practice, especially in collection triage, identity resolution, and D&D (“denial and deception”) at scale. The same broadness that makes “AI and counterintelligence” a timely topic also makes it easy for scholarship to drift from disciplined inference into plausible generalizations. Henry Prunckun’s article AI and the Reconfiguration of the Counterintelligence Battlefield, argues that authoritarian regimes integrate AI into counterintelligence more aggressively than democracies, generating widening disparities in surveillance capacity, strength of deception operations, and detection. That thesis is appealing, but the problem is that, as presented, it relies on conceptual stretching, not ‘real good’ operationalization, and OSINT constrained attribution, which together make the conclusion stronger than the evidence can reliably support.

Conceptual slippage: counterintelligence becomes a synonym for regime security

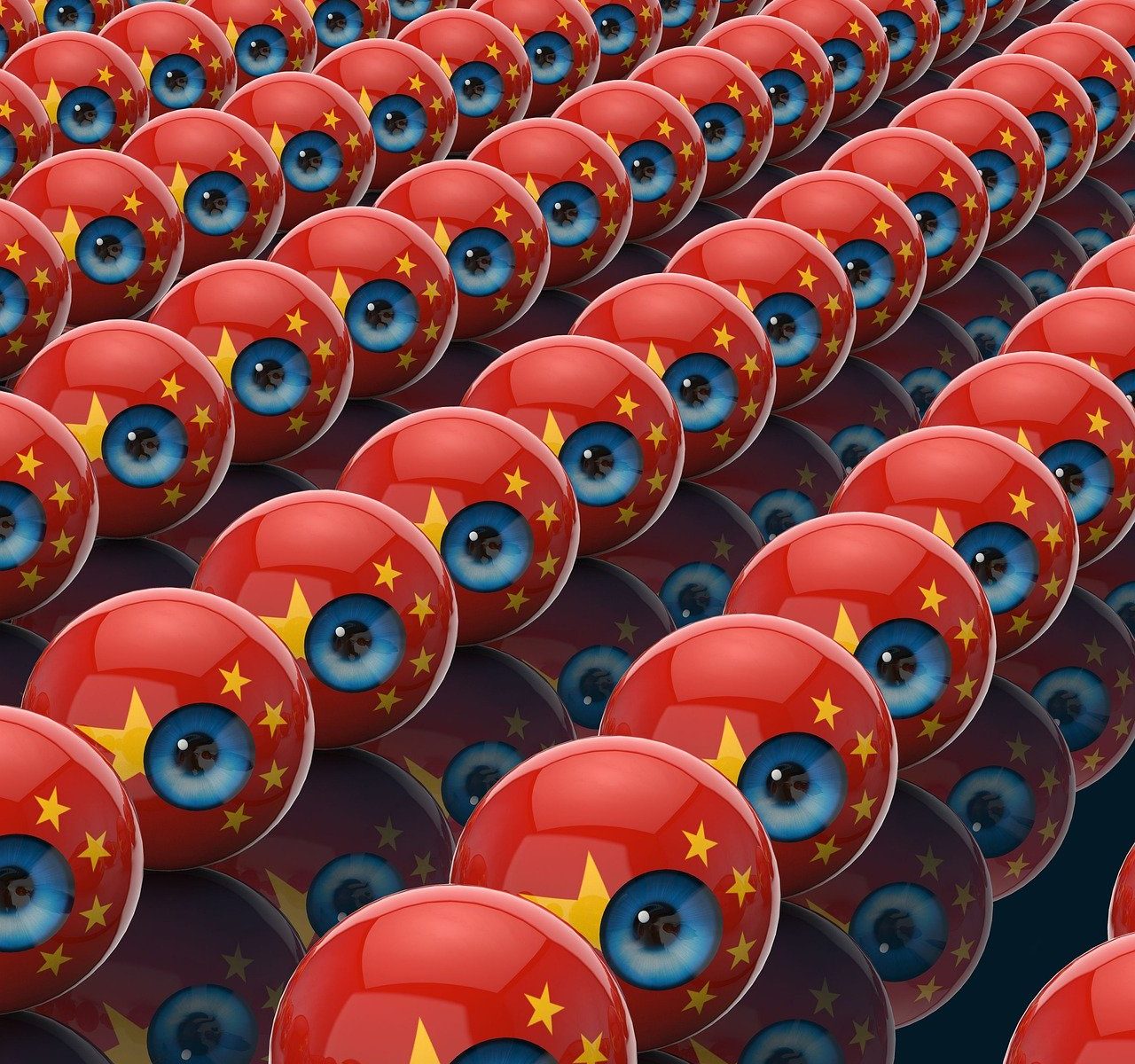

The article offers an expansive definition of counterintelligence, including hostile intelligence operations by FIS, non-state actors, and internal threats. That definitional move risks conflating classic counterintelligence functions, such as detecting foreign intelligence services, running double agents, and protecting sensitive programs, with broad domestic security tasks, such as repression of dissent, censorship, and generalized surveillance. In the case studies, that risk becomes reality. China’s Skynet and Sharp Eyes are treated as counterintelligence infrastructure, yet the true purpose of these systems is “public security” and political control ( meaning “suppression”) through population-scale monitoring and data fusion. This is not counterespionage in the narrow sense (Peterson, 2021; He, 2021). Using such architectures as direct evidence of “counterintelligence capability” is contestable unless the article could demonstrate a specific, evidenced pathway from mass surveillance to demonstrable counterespionage outcomes. A good example might be the identification of foreign case officers, agent spotting, surveillance detection route patterning, or disruption of recruitment pipelines.

This matters because conceptual stretching lets the analysis “win” by broadening the dependent variable. If counterintelligence includes nearly all internal security functions, then authoritarian states will almost always appear “ahead,” because their legal structures permit scale and coercion across the entire society. A tighter approach would separate “state security surveillance capacity” from “counterespionage effectiveness,” then test where and how the two overlap.

Unmeasured dependent variables: adoption is not capability, and capability is not effectiveness

The piece repeatedly asserts an “uneven transformation” and “increasing disparities” between authoritarian and democratic systems. The paper does not clearly operationalize what “capability” means. Is it speed of deployment, volume of data, integration across agencies, analytic accuracy, disruption rates, or successful attribution of hostile services? Those are DISTINCT variables. Without an operational definition and observable indicators, the comparative claim becomes rhetorical rather than analytic.

Fortunately, the literature on predictive analytics is instructive. Government and academic reviews emphasize that predictive systems can help triage and allocate resources, but performance and fairness depend heavily on data quality, feedback loops, and governance (National Institute of Justice, 2014; U.S. Department of Justice, 2024). In real deployments, predictive policing tools have faced serious critiques for low accuracy and bias amplification, precisely because historical data encode institutional and sampling distortions (Shapiro, 2017; Alikhademi et al., 2021). The counterintelligence analogy is direct. If authoritarian systems ingest broader data and act on weaker thresholds, they may increase the velocity of suspicion generation without reliably increasing detection precision. So, “more AI” generates more alerts, more potentially nefarious interventions, and more error, rather than more validated counterintelligence successes. Unless the article can distinguish surveillance scale from validated performance outcomes, it confuses activity with effectiveness.

Causal inference is asserted, not identified

The article frequently implies causation, that AI enables preemptive counterintelligence, improves early warning, and accelerates counterespionage timelines. Yet in this piece, the causal chain is not established with process tracing evidence. Much of the language signals inference by plausibility, using formulations such as “reportedly,” “believed,” “suggests,” and “consistent with.” That can be appropriate in exploratory work, but lacks strong causal conclusions about “advantage” or “disparity” without a rigorous evidentiary standard.

A methodologically disciplined approach would specify competing hypotheses and explanations. They would demonstrate why AI is THE differentiator, rather than alternative drivers like expanded authorities, intensified human surveillance, party control over institutions, enhanced cyber hygiene, or increased resourcing. Robert Yin’s framework for case study research emphasizes analytic generalization and the need to consider rival explanations, not merely accumulate confirmatory examples (Yin, 2014). Not following the framework begins to look like one of those cognitive biases that we are taught to avoid. The article’s current structure tends to accumulate plausible examples of authoritarian digital control and then attribute the change in counterintelligence conditions to AI itself, when the same outcomes could often be produced through conventional surveillance and coercion supplemented by basic automation.

Case selection: the design invites selection on the dependent variable

The four cases, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, are justified partly by strategic AI application, active counterintelligence engagement, and OSINT accessibility. That selection logic is understandable, but it has consequences. It tilts the sample toward regimes that are shining examples of coercive security states. It excludes “negative” or less confirming cases that might constrain the inference. Social science methodologists have repeatedly warned us that selecting only cases where the outcome is expected will often bias comparative claims, especially when the study then reasons as if the cases represent a broader population (King, Keohane, & Verba, 1994; Seawright & Gerring, 2008). If Prunkun’s aim is build theory, he may want to say so explicitly and limit generalization claims. If the aim is an authoritarian versus democratic comparison, it needs either systematic comparative indicators or at least one or more democratic cases chosen by objective criteria.

This flaw is not just academic. The paper makes claims about democratic constraints, Five Eyes governance, and interagency “silos,” yet provides no parallel case evidence at the same granularity as the authoritarian ones. There is an asymmetric evidentiary burden. Authoritarian capability is described through many examples. Democratic capability is summarized through general governance constraints, . . . a classic setup for overstating comparative divergence.

OSINT dependence: acknowledged limitations, but high confidence attributions persist

The paper responsibly acknowledges OSINT limitations, including bias, misinformation, attribution gaps, and inference under uncertainty. Then the narrative proceeds to attribute specific AI-enabled activities to specific organs such as the MSS, FSB, GRU, MOIS, and the RGB, even while admitting overlapping roles and covert postures. This is a substantive vulnerability. The hardest analytic problem in intelligence scholarship is not describing a tool set, but attributing operational use to a particular unit with defensible confidence.

The OSINT literature is explicit that open sources can be powerful but are shaped by discoverability, platform biases, selective visibility, and analytic framing, all of which can distort both collection and interpretation (McDermott, 2021; Yadav et al., 2023). Triangulation helps, but triangulation among sources that ultimately derive from similar technical telemetry pipelines or shared reporting ecosystems can create an illusion of confirmation. The article would be stronger if it adopted a consistent evidentiary lexicon like “confirmed,” “assessed,” “plausible,” “speculative,” and then used that teminology to discipline claims about which agency did what, and with what AI component.

“Cognitive security” is promising, but under-specified as a threat model

The piece explains “cognitive security” as safeguarding the analytic process from distortion, synthetic overload, and eroded trust. That is a valid conceptual move, and it aligns with growing institutional concern about deepfakes and generative deception (particularly impersonation), synthetic identities, and social engineering at scale (RAND, 2022; CDSE, 2025; ENISA, 2025). The weakness is that the paper’s cognitive security discussion remains programmatic rather than operational. It describes effects, such as evidence stream distortion and analyst overload, but it does not specify the attack surfaces, such as data poisoning, provenance forgery, adversarial inputs to classifiers, synthetic HUMINT reporting, or deepfake-enabled pretexting. Without a more explicit threat model, cognitive security risks functioning as an exciting label rather than an analytic framework capable of generating testable hypotheses and practical mitigations.

Overstatement risk in cross-national characterizations

Some country characterizations are brittle. The claim that Russia does not use AI for extensive domestic surveillance, contrasted with China, is vulnerable because Russia’s internal security ecosystem has long invested in monitoring and control, even if its architecture differs from China’s camera-centric methods. When a paper makes categorical claims that can be challenged by counterexamples, it hands critics a free punch and distracts from the stronger parts of the argument. Good comparative work often relies on “relative to” claims rather than absolutes, unless the evidence is overwhelming.

My take? The main contribution is conceptual, but its conclusions outrun its design

The excerpt reads strongest as a conceptual intervention arguing that AI changes the conditions of counterintelligence, especially by enabling synthetic deception and stressing analytic trust. Where it becomes substantively flawed is where it implies comparative empirical conclusions about authoritarian “advantage” and widening capability disparities without operational definitions, without balanced case selection, and with OSINT-constrained attribution that cannot consistently sustain unit-level claims. The remedy is not to abandon the thesis. It is to narrow the dependent variable, define measurable indicators, discipline inference and attribution, and align claims to what the evidence and design can actually support. Absent those corrections, the argument risks becoming unfalsifiable. Authoritarian states appear superior because counterintelligence is defined broadly enough to include most internal security, adoption is treated as capability, and capability is treated as effectiveness. Prunckun’s point here may well be true. I HIIIIGHLY respect this author and his expertise, however addresssing these flaws would go a long way to proving his points.

Bibliography

- Alikhademi, K., et al. (2021). A review of predictive policing from the perspective of fairness. National Science Foundation Public Access Repository.

- Center for Development of Security Excellence (CDSE). (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Counterintelligence Concerns (Student guide). U.S. Department of Defense.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). (2025). ENISA Threat Landscape 2025.

- He, A. (2021). How China harnesses data fusion to make sense of surveillance data. Brookings Institution.

- King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton University Press.

- McDermott, Y. (2021). Open source information’s blind spot. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 19(1), 85–105.

- National Institute of Justice. (2014). Overview of predictive policing. Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Peterson, D. (2021). China’s “Sharp Eyes” program aims to surveil 100% of public space. Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), Georgetown University.

- RAND Corporation. (2022). Artificial Intelligence, Deepfakes, and Disinformation.

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308.

- Shapiro, A. (2017). Policing predictive policing. Washington University Law Review, 94(5), 1149–1189.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Criminal Justice: Final Report.

- Yadav, A., et al. (2023). Open source intelligence: A comprehensive review of the state of the art. Journal of Big Data, 10, Article 38.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.